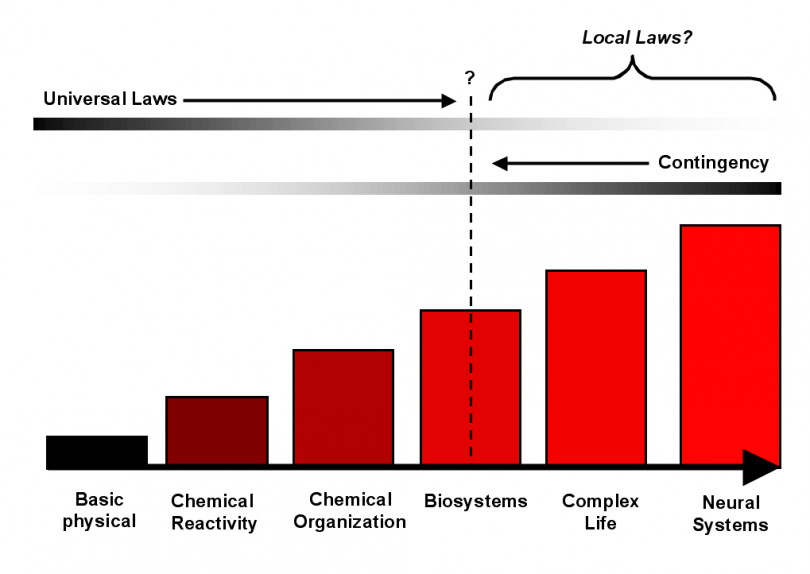

Alex Rosenberg is unusual among philosophers of biology in adhering to the view that everything occurs in accordance with universal laws, and that adequate explanations must appeal to the laws that brought about the thing explained. He also believes that everything is ultimately determined by what happens at the physical level—and that this entails that the mind is “nothing but” the brain. For an adherent of this brand of physicalism, it is fairly evident that if there are laws at “higher” levels—laws of biology, psychology or social science—they are either deductive consequences of the laws of physics or they are not true. Hence Rosenberg is committed to the classical reductionism that aims to explain phenomena at all levels by appeal to the physical.

It is worth mentioning that, as Rosenberg explains, these views are generally assumed by contemporary philosophers of biology to be discredited. The reductionism that they reject, he says,

holds that there is a full and complete explanation of every biological fact, state, event, process, trend, or generalization, and that this explanation will cite only the interaction of macromolecules to provide this explanation.

Such views have been in decline since the 1970s, when David Hull (The Philosophy of Biological Science [1974]) pointed out that the relationship between genetic and phenotypic facts was, at best, “many/many”: Genes had effects on numerous phenotypic features, and phenotypic features were affected by many genes. A number of philosophers have elaborated on such difficulties in subsequent decades.

The question then is whether Rosenberg’s latest book, Darwinian Reductionism: Or, How to Stop Worrying and Love Molecular Biology,constitutes a useful attack on a dogmatic orthodoxy or merely represents a failure to understand why the views of an earlier generation of philosophers of science have been abandoned. Unfortunately I fear the latter is the case. More specifically, his portrayal of the genome as a program directing development, which is the centerpiece of his reductionist account of biology, discloses a failure to appreciate the complex two-way interactions between the genome and its molecular environment that molecular biologists have been elaborating for the past several decades.

In earlier work, Rosenberg accepted the consensus among philosophers of biology that biology couldn’t be reduced to chemistry or physics. But whereas most philosophers saw this as a problem for philosophy of science, and for traditional models of reduction, Rosenberg concluded that it was a problem for biology, a problem indicating that the field’s purported explanations were neither fundamental nor true.

However, in his most recent book Rosenberg is more sanguine about biology. As the title suggests, the new idea is that recognition of the pervasiveness of Darwinism in biology will enable us to assert reductionism after all. Rosenberg is an admirer of Dobzhansky’s famous remark that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution:

Biology is history, but unlike human history, it is history for which the “iron laws” of historical change have been found, and codified in Darwin’s theory of natural selection. . . . [T]here are no laws in biology other than Darwin’s. But owing to the literal truth of Dobzhansky’s dictum, these are the only laws biology needs.

The suggestion is that something Rosenberg calls “the principle of natural selection” is actually a fundamental physical law. Natural selection, according to him, is not a statistical consequence of the operation of many other physical (or perhaps higher-level) laws, as most philosophers of biology believe. Rather, it is a new and fundamental physical law to be added to those already revealed by chemistry and physics. I won’t try to recount Rosenberg’s arguments for this implausible position.

The largest part of the book motivates reductionism from a quite different direction by defending the view that genes literally embody a program that produces development. Rosenberg introduces this view by recounting some work on the development of insect wings. There is a rather disturbing tendency in this exegesis to suggest an imputation of agency to the genes that are implementing this program. He says that the genes fringe and serrate “form the wing margin,” for example, and “winglessbuilds wings.” He also maintains that in Drosophila, “2500 genes . . . are under direct or indirect control of eyeless.” As the last two examples illustrate and Rosenberg explains, genes are frequently identified by what doesn’t happen when they are deleted. But Rosenberg seems quite untroubled by the dubious inference from what doesn’t happen to the conclusion that making this happen is what the genes “do” when in place. These reifications provoke a range of worries, but at a minimum, a defense of such ways of speaking will need to address another growing philosophical consensus to which Rosenberg is an exception, that the gene is a concept that no longer has an unproblematic place in contemporary biology.

Rosenberg does attempt a defense of the gene, but his arguments are unconvincing. The biggest problem is that he never says what he means by a gene. He refers uncritically to estimates of the number of genes in the human genome; although he does outline some of the difficulties with these estimates, he does not seem to appreciate their force. As a positive contribution, it appears that all he has to offer is the proposal that genes are “sculpted” out of the genome by natural selection to serve particular functions. The central point of critics of the gene concept is that functional decomposition identifies multiple overlapping and crosscutting parts of genomes. The “open reading frames” to which biologists refer when they count the genes in the human genome not only can overlap but are sometimes read in both directions. Subsequent to transcription they are broken into different lengths, edited, recombined and so on, so that one “gene” may be the ancestor of hundreds or even thousands of final protein products. Sophisticated would-be reductionists, such as Kenneth Waters, have tried to accommodate this point. Rosenberg seems just to ignore it as happily as he ignores most of the literature that has expounded the difficulties (for example, What Genes Can’t Do, by Lenny Moss [2003], and The Concept of the Gene in Development and Evolution, edited by Peter Beurton, Raphael Falk and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger [2000]).

The problem might have been ameliorated if Rosenberg had paid more attention to the increasingly diverse constituents recognized in the genome apart from the genes he needs to run his programs. The lack of concern with the genome is highlighted, for example, when in the course of a single paragraph he says that sculpting of the genome by natural selection has resulted in “a division mainly into genes” and refers to 95 percent of the human DNA sequence appearing to be “mere junk” (another hypothesis that has been widely rejected). It is conceivable that Rosenberg means to define genomeso as to exclude the junk, although I have never encountered such a usage before. What is clear, though, is that he sees the genome merely as a repository for the informationally conceived genes supposed to run the developmental program. Attention to the increasingly understood complexities of the genome as a material object would have made the misguided nature of the enterprise much clearer.

A further problem is that some of the biology in the book is dated. For example, Rosenberg says that “there are about 30,000 to 60,000 genes in our genome,” but in fact there is a fairly stable consensus now that the number is about 23,000. More striking is his remark that alternative splicing is “uncommon but not unknown,” whereas it is actually widely accepted that such splicing occurs in more than 70 percent of human genes. Although Rosenberg has researched some biological topics in detail, the book contains other lapses as well. He appears to be unaware, for instance, that methylation occurs in contexts other than sexual imprinting. And I was struck by his remark that the world is now mainly populated by sexual species; in fact, the overwhelming majority of organisms now, as ever, are prokaryotes and (relatively) simple asexual eukaryotes. It is admittedly difficult or impossible to stay fully au courant with the latest in molecular biology, but a careful reading of the manuscript by a practitioner would have been very helpful.

Because I have been involved for many years in criticism of the earlier orthodoxy that Rosenberg continues to defend, it is not surprising that I am unconvinced by his reactionary argument. And it is of course very often a good thing for philosophers to confront the orthodoxies of their discipline. But the standards for undermining orthodoxy are inevitably high, and Rosenberg does not come close to meeting them.

The subtitle invites us to learn to love molecular biology. Many of the philosophers whom Rosenberg’s views contradict greatly admire the achievements of molecular biology. Love, however, is well known for being blind. I would encourage Rosenberg to settle for admiration.